SOME DEVOTIONAL RESOURCES

SOME DEVOTIONAL RESOURCES

AND AN EXTENDED REFLECTION

O Jesus, Master Carpenter of Nazareth, who on the cross, through wood and nails, worked our whole salvation; wield well your tools in this your workshop; that we who come to your bench rough-hewn may by your hands be fashioned to a truer beauty and a greater usefulness, for the honour of your holy name, Amen

PRAYERS

We recall those who did their jobs on that Friday long ago

prayer from the United Methodist Church, USA

Strengthen us to face the very worst in our world

prayer from the United Church of Canada

PRAYER STATIONS

Stations of the Cross PowerPoint - from CAFOD (the Catholic Agency for Overseas Development): 'as we reflect on the final journey of Jesus, leading to his death on the Cross, we also contemplate the lives of our sisters and brothers around the world living in extreme poverty' (if you are using a tablet or mobile, this PDF version will work best; if you are using a desktop or laptop computer with PowerPoint, this PowerPoint version will work best).

EXTENDED REFLECTION | 'Here hangs a man discarded'

You can read the text of Brian Wren's hymn here.

REFLECTION TRANSCRIPT

In some parts of rural North Lancashire it has become traditional to have a scarecrow competition over the Easter holiday, though, of course, it won’t be happening this year. People will miss the display of brightly coloured, gauche-looking figures, designed to scare away the birds – not, in this case, in the fields, but outside the pub, beside the parish hall, in people’s gardens: for visitors to come and admire and be amused by in a carnival atmosphere. The hymnwriter, Brian Wren, also associated Easter and scarecrows in his hymn Here hangs a man discarded (Singing the Faith 273). But the scarecrow that Brian Wren has in mind is an altogether more pathetic and nonsensical figure. And Brian Wren dares to use that scarecrow as an image of Jesus Christ.

I guess it was the arms of the scarecrow stretched out on an old broomstick that first reminded the hymnwriter of the arms of Jesus spread wide on the Cross, his wrists nailed to the cross piece. But I guess there will also be deeply embedded folk memories of scarecrows as a part of the English rural landscape. And the scarecrow in the Wizard of Oz: no brain and he doesn’t know the way. The scarecrow looks like a signpost but is a ‘nonsense pointing nowhere’. It’s dressed in clothes that people have worn out and thrown away and have no further use for. And nowadays we have no further use for scarecrows. Electronic bird scarers have replaced them!

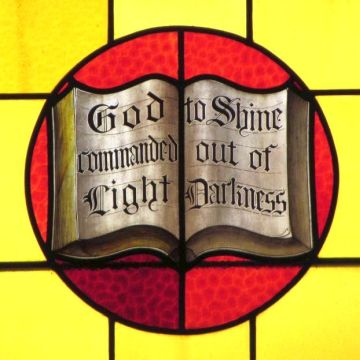

What a strange image to use for Jesus and the Cross. It’s not an image that comes out of the bible, but maybe it’s not far from the way that St Paul pictured the Cross. He described the Cross of Jesus as a scandal: ‘a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to non-Jews’ (1 Cor 1:23). For Jews a ‘crucified Messiah’ was simply a contradiction in terms: they simply couldn’t accept that a Messiah could be crucified and executed in this most degrading way. Crucifixion was for common criminals and political agitators in the Roman Empire. An early anti-Christian graffiti portrayed Jesus as a crucified ass (it comes from the third-century: ‘Alexamenos is worshipping his god’).

The stigma of crucifixion is something that people tend to airbrush out these days. The cross is treated as a fashion accessory, a beautiful item for beautiful people. But, originally, it was a thing of great ugliness for people who were disfigured and disjointed: people in need of wholeness and salvation. Christians have learnt to see the Cross as a thing of beauty, because it is there that we see and experience the depth of God’s love, the arms of God’s mercy and God’s generosity spread wide to catch us in their embrace. But, let’s for a moment stay with the hymnwriter and the sheer scandal of the Cross and try to enter into what Paul meant when he said that: ‘God’s foolishness is wiser than human wisdom’ (1 Cor 1:25). What is this deeper wisdom and how does it help us to make sense of our lives?

The scarecrow in Brian Wren’s hymn is a symbol of your experience and mine, as well as of the crucified Saviour. ‘Here hangs (one) discarded’. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many people have been feeling isolated and anxious. Normal life for most has been put on hold. Ordinary routines have changed massively. Those unable to work at the moment may have lost a key sense of their identity. Those having to self-isolate at home may easily begin to feel that life is going on elsewhere, without them. For some, self-isolation will have to continue even once the lockdown begins to be lifted – they may feel they’ve been left high and dry whilst life goes on somewhere else, like a scarecrow hoisted high, ignored by those hurrying by to where the action now is. Perhaps this Good Friday people might be able to identify even more readily with the one who hangs discarded on the Cross.

Or, maybe, thinking about more normal times, you feel ‘discarded’ because you’ve been passed over for promotion, your skills unrecognised or out-of-date. If a relationship has broken down or come to an end, again you may have felt discarded, thrown on one side. Nowadays people talk about being ‘dumped’ by their partners. Or, perhaps the children have grown up, you’ve retired maybe, and you start to feel as if you don’t matter any longer.

We can use our experience of feeling discarded to help us empathise with the discarded people of our country and our world.

But empathy is hardly enough. Jesus was ‘led like a lamb to the slaughter’, a man discarded ‘and acquainted with grief’. And it’s in his Cross that we dare to hope against hope.

There are many ways of understanding the Cross, but one powerful way is contained in the words of this hymn. For it speaks of the love ‘that freely entered the pit of life’s despair…and suffer(ed) with us there’. Jesus hung there not high above the despair of the world, but as one discarded, his life ‘drained out’. Which means that we can never sink so low as to be beyond the love of God. For God has been there too, in Christ. God became fully like us, so that we might become fully like him. However foolish it looked at the time, the story of Jesus did not end at the Cross. The man discarded, the scarecrow hoisted high, was raised much higher, raised from the pit of death itself.

But the Cross works not by, as it were, airlifting us out of trouble, but by staying in there with us, suffering alongside us. I guess the last words of the hymn come as a surprise. In Hollywood mode we would ‘hold the hand of promise and walk into the light’ … or the sunset. The hymn instead talks of walking ‘into the night’. Night has to come between Good Friday and Easter, but with it comes the hand of promise, the faithful everlasting arms of God, even when we can only make out the shadow of God’s hands.

There’s a little village in the Derbyshire Peak District that draws thousands of visitors each year, often for repeat visits. One episode in its history fascinates people and, for me, resonates with Brian Wren’s hymn. It’s the village of Eyam. The year was 1665 and the Great Bubonic Plague was raging out of control, rather like COVID-19. In the autumn of 1665, a box of cloth from plague-infested London was delivered to a tailor. It was the start of a twelve-month epidemic which swept through the village and killed 267 people, leaving just one in four of the total population alive. So far, just a tragic story, but today’s visitors often find the rest of the story quite awesome.

Led by their young Rector, William Mompesson, the villagers decided to seal themselves off from the outside world to prevent the plague spreading to neighbouring villages. Virtually no one left the village and no one was allowed in. They imposed a quarantine on themselves, and grimly waited it out as the infection took its unpredictible course. One of the fatalities was the Vicar’s own wife. Food was left for the villagers on the parish boundary high up on the hill above the village, and paid for by coins which had been dipped in vinegar to disinfect them. Corpses were buried quickly near their own homes. It was reckoned too dangerous to transport them to the churchyard or to gather for worship in the church.

It was a tremendous act of collective self sacrifice, but as a result no case of Black Death was recorded anywhere else in Derbyshire. A group of people who chose to suffer alongside the discarded and share their despair, that others might be saved. A parable perhaps for us today, as we contemplate, this Good Friday, the Cross of Jesus and the man ‘discarded’.

Philip Richter 2020